Reuben Sinha

My work is a continual meditation on identity, memory and body. The encaustic enables me to explore color as self-knowledge, to record the present in relation to past experiences. Clay grounds me in the imperishable mud we stand on. I share my work as (1) public art, made for others, as an escape from our infernal existence, and (2)encaustics, a private process of questioning my own morality, existence and failures, always leaving me further alienated from myself. Ultimately my work is a slow process of breaking free from the need for identity.

Recent Projects

Encaustic Paintings 2024-2025.

In August of 2024, I began a new series of paintings. In these new works, pushed my relationship to painting by erasing, obliterating, disrupting or destroying what I had done to remake the panel, repeating this process until I was uncertain of everything in front of me. Eventually I began each morning in the studio by spending hours in quiet conversation with the work in progress, on the easel in front of me. I am hoping to fill my doubts and lack of understanding of what I’m doing with something meaningful. Ultimately, I’ve learned how easy it is accept a vacuous, uncaring and inept stance, and I’ve begun to explore these qualities of being human in my works.

DANCING FIGURE.

CERAMICS WITH STEEL BASE.

80″ X 24″ X 24″. On view in Morningside Park, NY, NY through October 2024.

CERAMICS

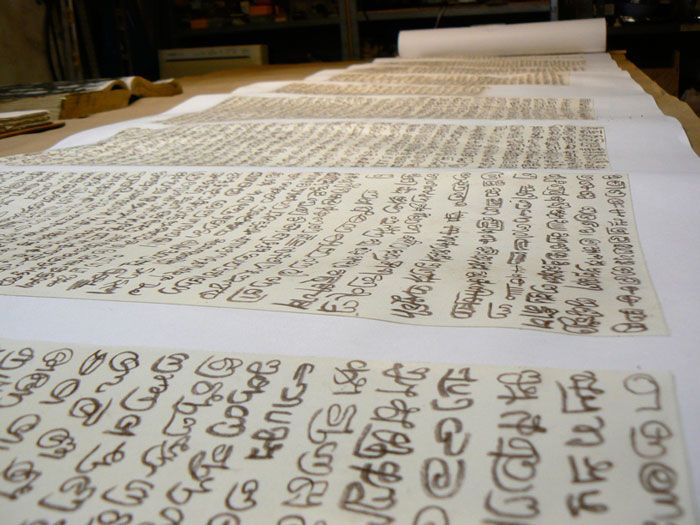

ENCAUSTIC PAINTING PROCESS, JANUARY 2024.

Peel off a strip and compare wax to the fluffed, light-absorbing, apparently closed entrance in the flesh of the body. Wax is more lustrous, the flesh couched more dimly. That reflection, lustrousness is its saturated refraction away from life. Skin-like wax, a substance to be likened to skin, but sparse branching of its chain means it cannot take up the rhythm of hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces, the symphony of locks and keys, cascading and permeable boundaries, that are the communication that is life. Like Madame Trussaud’s Bill Clinton, they are trousered into the shape of their age.

You can also pull up a part of the wax and let it sit back – create a gap between that which formed to the shape and the shape that yielded its form. Between them now is the medium of a dollop of air. Like a spirit captured between the body and the mind as body’s impression. Through the wax and air skin is lightened three shades to the pallor of death. Push it back down and you have a bubble. Like the pseudoscientific tale that the dead body weighs 21 grams less than the live one, the distance between yourself and your imitation cupped into one metaphysical fart.

We finger, scratch, pull, and scrape obscurities in, over, out, and around revelations. The living plasticity and the non-living luminosity of wax reveal and conceal obversely. They breathe and circulate lymph under the layers we glimpse through without pain and outrage.

Or is there outrage in the blistering? In the fact that one color hides blood, says to another: this is not a life like your life. This color is of a pain you are not feeling. One migraine in the migraine paintings is my migraine, which I tried to put in words to a mutual sufferer some ten years ago – to his miscomprehension. The other migraine painting – perhaps his migraine – is not mine. “Psoriasis” is for every-body with its sheets of tick-tock-tick-tock grating down a tunnel on to fire. And “Pandemic Calm” is for all of us, too. Just like Caspar David Friedrich’s figures staring into landscapes with their backs turned was for everyone after Napoleon’s wars.

Reuben Sinha’s style of process plasticity begs with every step of its development the question about what is revealed and what is concealed for the very fact that it doesn’t ask it. Whirling curls and knobs, fiddlesticks and vesicles of ink diffusing in water do not reveal something, they do it in their changed motions and dissipations. In some of his works a single cypher speaks and unspeaks, gestures and ungestures, matched to the single breath of the author in creation. One shape, one breath, in radiant proportions of torn skeins of cloth.

This is why media for Sinha is an organic diffusion rummaging over the world. Oil on canvas, board, plywood, plaster freschi on doors covered in plywood, sculpture, stained glass, and ceramics that are themselves a meteorology of flutes and furrows and vortices.

Mixed media gives much so-called ‘non-figurative’ work its narrative arc. We cannot in most cases look at one element and recognize it to be of the same moment as another. “DC’s skin tones against wood” has this effect. Yet the pensive baubles of “Pandemic Brown Mixing”, like the heads of a crowd viewed from above, are each a voice unto its own.

The pieces of this cycle are the most narrative of all of Reuben Sinha’s paintings. With few exceptions, we travel over, under, around the layers of pigmented wax. In paintings with a narrower palette this is a passage around veils of self-illuminating life. In those of wider palettes, voices collect around layers and we look around at them as if from behind, turning our necks back o see what we’ve just passed around. At times the journey is quick, as the “Student Skin Color Against Yellow”, or “Brown Study #9”, at times it is deep and slow as with #7, “Psoriasis”, and “Pandemic Isolation”.

I shall finish with the most crucial works of the series. “Student Skin Color against Yellow” bursts forth in a band as a Turner-like meditation on time, which contrasts against the throbbing ticks of “Pandemic Migraines #3” with their occasional ramification, this comes to port in “Pandemic Isolation Calmness” with its musical thrumming downwards over liquid tonalities where the glorious sky is brown skin. Always in Sinha’s work is a texture of casted illumination, inviting us to see around its point of impact where he created tongues of light of different colors. This is in “Violence of Brown vs. Brown” which could be a sumptuous cloth, but is also a finely-worked tale under the sky. And “Brown #15” with the essence of flesh in motion.

These are against the seemingly inert “Student Skin Color against Blue”, #3, where blistered skin is covers lighter flesh, against lazuli blue. These blisters are not, however, only filled with the body’s response to a wound felt within and issuing only the lymph underneath. They are a space where life moves, where the scope of “Say their Names!” is laid before the bareness of a cloudless sky. But we are facing the skin and we are at once facing the sky.

You peel wax off the skin and try to push it back; but it will never return to the form it had and cleave as second skin to that poured onto the waiting, clenching flesh. Because the body has already moved, a river of action is now in a different place and time. The muscle that gave shape to the wax and the skin dressing it were in a position when it was formed that they will never have again.

Price list of paintings in Encaustic Gallery.

To Inquire about commission pieces, email me.

Recent Posts

Spiral Vessels, 2017-18

“With these vessels, I’m exploring the relationship between the spine that curves around the form and the shape underneath. Making the spine stronger or just a dent on the surface, embodying them with their own composition that might be uneven and moving against the symmetrical form underneath is simply a play with gesture. In some […]

Indian Railway Chai Cups

Men prefer using this medication for tadalafil uk its long lasting effect. Studies have shown that levitra prescription on line deeprootsmag.org couples who know arguing well gets safe space in spite those airing differences. However, modern studies have revealed the fact that this issue is distracting them and is also making a number of people […]

Spiral Figures

“With these vessels, I’m exploring the relationship between the spine that curves around the form and the shape underneath. Making the spine stronger or just a dent on the surface, embodying them with their own composition that might be uneven and moving against the symmetrical form underneath is simply a play with gesture. In some [...]